We are all delighted to announce the welcome arrival of baby Zephyr!

Many congratulations to his HWC mum, Lily, and all the family. xxx

(Cheers and rapturous applause!)

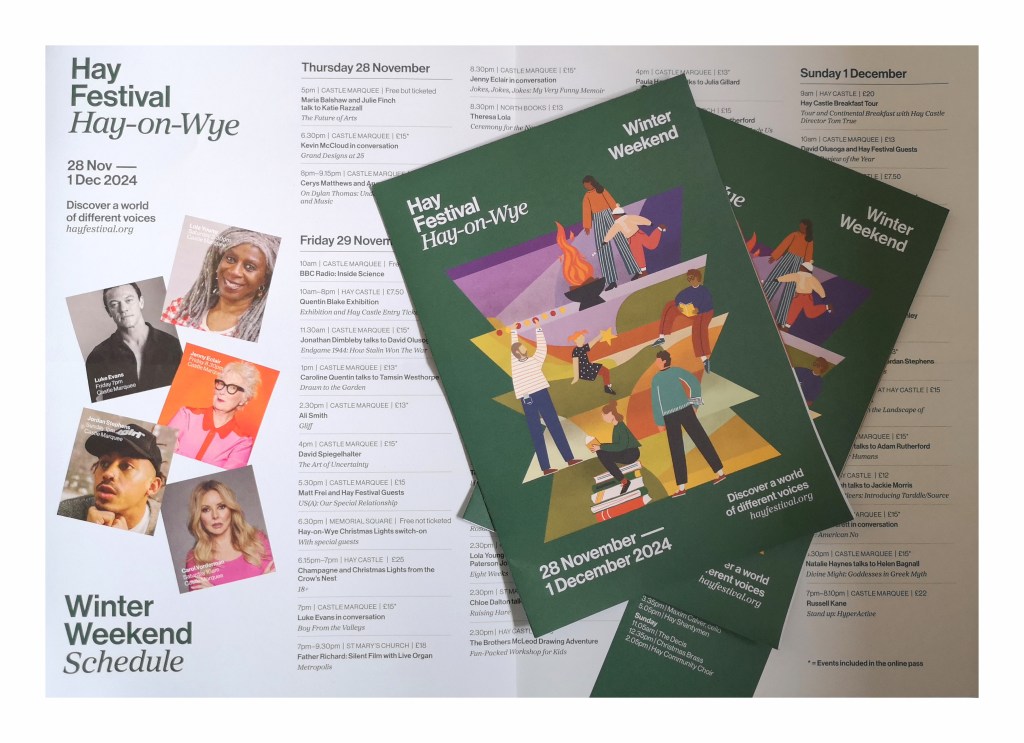

Hay Festival Winter Weekend

It’s less than a month to go before Hay Festival welcomes us all to it’s Winter Weekend, 28th November – 1st December 2024. It’s definitely something to brighten the darkening days and place us firmly on the road to seasonal celebrations ahead.

If you haven’t booked your tickets yet, please check out their website – CLICK HERE If getting to Hay is not possible, then there’s a great selection of digital events which you can access from the comfort of your laptop.

Those who can make the journey, don’t forget the Christmas Lights will be switched on by wonderful Welsh Actor and Singer, Luke Evans along with our soon to be announced Citizen Of The Year. Join the party atmosphere in the town square on Friday 29th November.