We are delighted to showcase the top two entries as well as the judge’s comments of our most recent competition, The Richard Booth Prize for Non Fiction 2024.

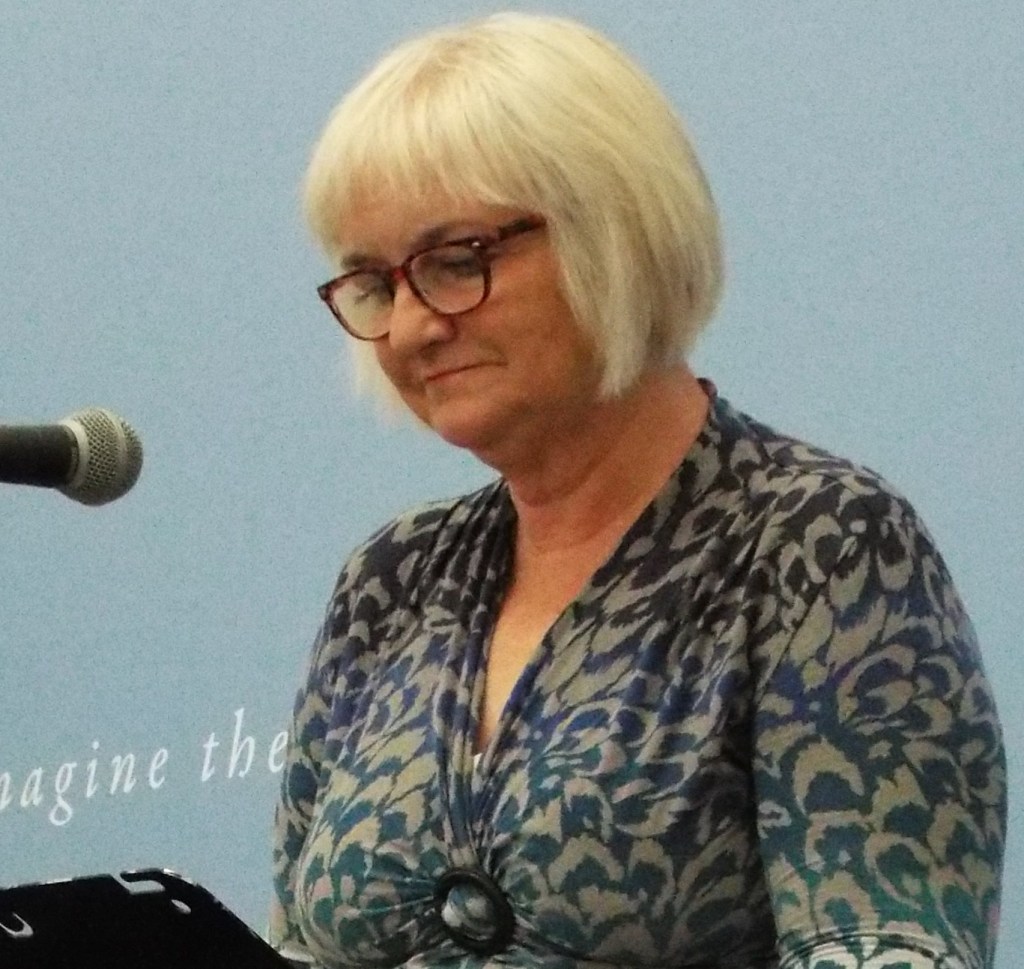

Our judge this year was the incredible Dr. Alwyn Marriage.

Dr. Alwyn Marriage is a poet, lecturer and writer, a member of the Society of Authors, and Managing Editor of the publishing house, Oversteps Books. She is also a Research Fellow in the School of English and Languages of the University of Surrey.

Here are Dr Alwyn Marriage’s remarks.

“Thank you for inviting me to judge this competition.

I enjoyed reading all the entries. I am more used to judging poetry competitions, so had to consider what criteria would be appropriate for judging a non-fiction competition. In poetry, one has to consider both form and content; but non-fiction is also an art form, so in judging these short pieces, I was, similarly, looking for quality in both form and content.

Content

1. Interest. The piece of writing must attract attention, pique the reader’s interest. This might be either by the choice of subject matter or by the use of a striking image early on. However, while the degree of interest of the subject matter is obviously important, it is by no means the only necessary quality.

2. As part of that, the deft use of suspense can (though doesn’t necessarily) contribute to the interest. In some of these pieces, the writer played successfully with suspense (eg, Spooked, Only shaken). Suspense is fine and can be exciting, but in general it’s also good if there’s some resolution, rather than the reader being left unsatisfied or baffled at the end.

3. Description and detail. There were some very enjoyable vivid descriptions among these pieces. Sometimes I wanted a bit more. eg in Mountains I would have liked to read a little more about the writer’s time at the top of Mt Blanc. But on the other hand, too much detail can sometimes be distracting. Tiny points that excite the writer won’t necessarily appeal as much to the reader who hasn’t shared the experience. So, as ever, it’s a question of getting the balance right.

4. Good nature writing always goes down well, and there was some of that in, for example, Only shaken and in The Awakening.

Form and language

In general, people buy books for the content, but will be put off if the writing is poor, boring or careless. There are, however, books where the writing is so delightful that the content hardly matters. For example, I’m not a great fan of historical novels, but the quality of prose by someone like Maggie O’Farrell can tempt me to embark on journeys into the past with her.

1. You are aiming to produce a work of art, so attention should be paid to form and shape. as well as to content. Writing a piece like this is not just an invitation to reminisce. The first and second prizes both had pleasing shape, which pushed them up the stakes.

2. Language matters! So it’s worth taking great care over language, spelling and grammar. If necessary, get a fresh pair of eyes to look at a submission before sending it in. For example, either check spelling yourself or use a reliable (non-American) spellcheck. Micro-computer trolley was really interesting, but would have benefited from careful editing and a spellcheck. Also in Mountains, there was a surprising change of tense in the middle for no apparent reason, which stuck out like a sore thumb.

3. Awareness of tone. Aim for a consistent tone, except when you want a special effect. The winner almost got knocked off first place by one infelicitous interpolation. However, s/he was saved by the quality of the rest of writing.

4. Respect for potential readers. Avoid any hint of blasphemy, misogyny, homophobia, racism, etc.

5. Editing and polishing – Go over the piece more times than you think necessary and don’t allow any mistakes, omissions or rambling passages to survive. For a start, polish your first sentence until it shines. It’s got to grab attention and promise a satisfying read. However, having done that, it’s obviously important to maintain the initial impact right through to the last word. Speaking of which, endings can be tricky, so work at those, too. The piece shouldn’t just fade out as though you’d run out of energy or ideas.

6. What might help you to write better – It’s worth considering what the author does when embarking on a new non-fiction book (which I’ve just done!). At one level, she is keen to get her ideas out and share them with other people, so of course the content is of prime importance. But how does she also produce beautiful writing worth sharing? I think the answer to that must be by reading widely and writing regularly. I know that we are talking about prose writing, but I would also advocate that reading, enjoying and maybe occasionally writing poetry is likely to enhance enormously the quality of one’s prose writing. It will help develop a musical and graceful style which should overcome any reticence by a potential reader to engage with the subject matter.

In conclusion, thank you for entering the competition and for sharing your pieces with me. There was lots of variety in style and content, and I enjoyed reading them all.

I look forward to discovering what the gender distribution of the writers was, as I felt there were slightly more entries by men than by women. It will be interesting if I got that wrong!

Alwyn Marriage

August 2024″

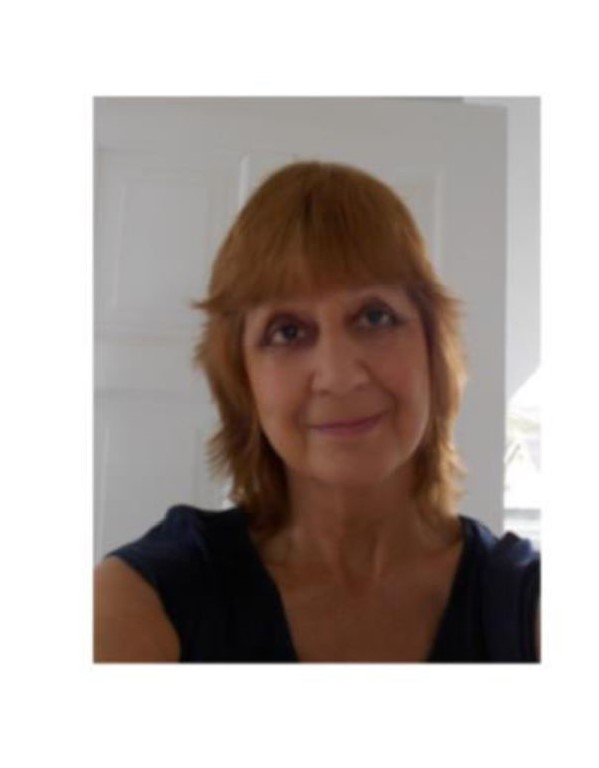

With the above comments in mind, here firstly, is the winning entry Five Photographs, by Jean O’Donoghue

Five Photographs.

1. It’s the classic, kitschy baby photograph. I am lying on my fat little belly on a furry rug. My buttocks shine like a new moon. I am about six months old and have just conquered the art of holding myself up on my arms. My mum will later tell me that it took an hour for the photographer to get the picture. She had to spend that hour calming me down from my squealing objections to having my clothes taken off. My face betrays the fact that I am not happy, though the squealing has halted temporarily. My face is one of bemusement and disgust, a facial expression that will reappear later on in my future. I don’t remember the photo being taken!

2. Standing in front of a glittery Christmas tree. Age probably five, at Grandma’s house. My smile the widest possible, my hair caught with extravagantly large butterfly bows. My hands are holding outstretched the white bright net skirt of my fairy outfit. The photograph is black and white of course, captured by an uncle who has just mastered the skill of basic photography. Next to me is my baby brother, much smaller, wearing a cowboy suit too big for him. He smiles as well and put together we are a picture of innocence, joy and pride.

3. It is taken on a wide, wide beach in Bridlington or Scarborough or Mablethorpe. Myself, aged around eight, and my brother have created a motor boat out of the damp sand and we are seated together waving at our Dad. Our arms are getting tired as he fiddles about with an exposure meter and our faces come to look somewhat less joyful and relaxed. At last the shot is made. But there is another one from round that time of seaside holidays. It is a small, murky brown sliver of film encased in an ivory coloured cardboard frame. I remember this being taken. It was by a peripatetic photographer on the prom who promised to have the photograph produced instantly, for only ten bob. This is not the sort of thing that my parents would usually indulge in but maybe it was the whiff of invigorating ozone, or the exhilaration of holiday time that led them to say “yes”. It did seem like magic when the photographer produced the finished article and it was less brown and more decipherable then and portrayed the four of us, arms linked, advancing on the photographer with big smiles after he had chided “cheese!”

4. It is taken in our back garden at home, in colour this time! Maybe I am thirteen, and still the smile and the pride are there. I am wearing my full Girl Guides uniform and I am saluting as if at the start of the parade. We have been rehearsing for this parade for weeks. It is a big deal as Lady Olave Powell is coming. My belt is shining, as are my shoes and my guide badge has had an extra shining up as well. My sleeves are full of badges for laundress, for navigation and campfire lighting. My brother is not in the picture, but I sensed he was there just out of sight, making fun of me. He is no longer little but an impressive manlet of steely sinew. Also a persistent mocker.

5. Fifteen now, colour again. Girl Guides long gone. If it were thirty years later, I would be a Goth, but since they are not yet invented I have to content myself with a surly snarl that my baby photo presaged. I don’t want to be photographed and neither does my brother who I am holding in a not so sisterly grip around his neck. I know that he will get me back for this, and am already preparing to escape. I am wearing my grandmother’s pinstripe suit from the forties, which I had bullied my mother into customizing. On my feet are long boots from a charity shop even though this is July. On my head is a striking trilby. My mother cannot bear to be seen with me in town.

These five photographs are in a soft leather pouch that I found in her wardrobe when my mother died. I still have the trilby.

2nd Prize went to The Whole Truth, by Val Ormrod.

The Whole Truth

If a writer chooses to write memoir, should we demand the whole truth and nothing but the truth? Should a reader expect a writer to reveal all in order to fully engage with the story, and does the author have any obligation to fulfil that expectation? How up close and personal does a writer have to allow the microscope?

In today’s culture where ‘no holds barred’ revelations are common and where the freedom of the internet has opened up an avenue for everyone to disclose details of their lives and express their views, however illogical, biased or even defamatory, do readers expect the same? Does a reader feels cheated if they think the narrator is withholding something from them or not being honest about their emotions? The public seem to have an almost insatiable appetite for other people’s stories, especially when they are celebrities.

In August 1929, Sigmund Freud scoffed at the notion that he would do anything as crass as write an autobiography. He maintained that a psychologically complete and honest confession of life, on the other hand, ‘would require so much indiscretion (on my part as well as on that of others) about family, friends, and enemies, most of them still alive, that it is simply out of the question. What makes all autobiographies worthless is, after all, their mendacity’.

But do some writers conceal as much as they reveal? Can anything be withheld, kept private?

This short essay does not attempt to answer any of these questions, rather it invites the reader to explore these more fully by reading this genre. Although there is insufficient space to examine them any more fully, it looks briefly at three memoirs, very different in style but all dealing with grief.

In H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald deals with the pain from her father’s sudden death by undertaking the training of a goshawk.

In an interview prior to publication of her book, she was asked how she felt about having put so much of herself on the page. She confided that:

‘The only way I could write about grief was to be brutally honest about how it felt.

I’m definitely nervous, now, about having put it all out there, but there wasn’t any

other way to do it; when I tried to dissemble or hold back, the words wouldn’t come.

But I’m not quite the person in the book any more, which makes it feel less exposing.

I was so deep in grief back then I saw the world very differently.’

She describes the book as a depiction of ‘my own struggle with grief during the difficult process of the hawk’s taming, and my own untaming’. Her grief is never overplayed, nor is it sentimental, but is restrained and often understated – a self-awareness of what she is facing. When the book moves on to meeting the challenges of training the hawk, the author shows her vulnerability and is not afraid to admit her feelings of inadequacy.

In his memoir Do No Harm, Henry Marsh is unflinchingly honest about the emotions of the surgeon, the fear, the responsibility and the guilt when an operation is not successful, especially when a mistake has been responsible for the failure. Mistakes are made in any profession, but most do not involve the catastrophic results that neurosurgeons must face at these times. Marsh wrote the book towards the end of his career when, rather than feeling proud of his many successes, he is haunted by the failures that inevitably result from such intricate and dangerous microsurgery:

‘The more I thought about the past the more mistakes rose to the surface, like

poisonous methane stirred up from a stagnant pond.’

The stated aim of the book is to reveal the conflicting qualities of detachment and compassion that a surgeon requires to be able to do their job, and the human difficulties that doctors face. He is aware of how much patients need to believe in the surgeons who are treating them, noting:

‘It is not surprising that we invest doctors with superhuman qualities as a way of

overcoming our fears’.

He feels the heavy weight of that responsibility. Paradoxically, the more he needs to reassure a patient, the more anxious he becomes himself. He knows that if he dwells on the possibility of failure too much, he will not be able to do his job, because he needs to believe in himself too.

Marsh reveals himself as a sensitive man who suffers for his mistakes and is only too aware of the physical and psychological damage that can be inflicted on both patients and their families. Seeing patients that he has operated on now in a vegetative state, he is tormented by their faces:

‘the look of the damned in some medieval depiction of hell’.

In writing the book, Marsh is perhaps revealing the very things he has tried to conceal in his professional life when he needed to maintain detachment in order to carry out his surgery. In spite of his evident passion for this work, he exposes himself as a human being who suffers the same crises of confidence as any other mortal. With perhaps too much modesty he asserts:

‘I hope I am a good surgeon, but I am certainly not a great surgeon.’

The Iceberg by Marion Coutts begins with:

‘Something has happened. A piece of news. We have had a diagnosis that has the

status of an event. The news makes a rupture with what went before: clean, complete.’

This passage sounds on the surface as if it is highly controlled, distanced from emotion. The contrast with what she is feeling could not be greater. The author goes on to reveal the story of the next few years with a poetic eloquence that is lyrical and intensely moving.

The scenes are presented to the reader as if through a camera lens, intense and zoomed in to the heart of the story. It is a profoundly moving depiction of the decline of art critic, Tom Lubbock and the effect this had on his wife and young son.

‘Ever so slowly we inch back to the barely functioning platform that is our life…Cancer scarcely allows you time to look at it, let alone get used to it. Tom’s is a high-speed disease with full, motorway pile-up repercussions.’

Other writers also feel the need to express their personal story but conceal it within thinly disguised ‘fiction’ and it has been suggested that many first novels by fiction writers relate closely to their own personal thoughts and experiences. This is a fine line and begs a number of further questions: What is reality anyway? How reliable is memory? How much of an experience is an individual’s own interpretation of events rather than a bald recounting of that experience?

Every time an anecdote is recalled and repeated, whether it involves an event or a conversation, there is the possibility of this being altered. This can be in subtle or obvious ways; the changes can be minor or substantial, completely altering the tone of it, like Chinese whispers. And in every one of us, no matter how honest we think we are being, there is the Russian doll syndrome – different versions of our lives that sit within us.

In conclusion, whichever way they are presented, stories continue to fascinate us. All of us who write must continue to be grateful for that.

Many congratulations to our 2024 winner, Jean O’Donoghue and our runner up, Val Ormrod for their fantastic pieces. Also, huge thanks to our judge, Dr Alwyn Marriage for her detailed comments, which I am sure we will all find useful going forward in our writing work.

Our annual Hay Writers’ Circle AGM takes place on Tuesday 1st October, a little later than usual so look out for updates in our next article, along with the 3rd prize and commended pieces from the Non Fiction competition too.

And Finally….. Hay Festival Winter Weekend!

The programme is out! Hooray!

For more information go to Hay Festival website, or if you are in Hay-on-Wye programmes are freely available at most places around town – so grab your copy today!